Getting real about the utility of social media for public transit

Some consultants and advocates claim that social media is significantly transforming how transit agencies communicate with their passengers and market their services. Social media has been a reoccurring topic in transit conference programs for several years. Frankly, I believe the potential of social media for transit is often oversold — following a reoccurring pattern of hype around “the next thing” in technology. I’ve composed this blog post as a way of organizing my own thoughts, sifting real opportunity from hype, and attempting to contribute to a transit industry discussion about the value and utility of social media.

What is social media and the social media industry?

Leading social media platforms are Facebook, Twitter, and Google+. There are also sites dedicated to pictures and video like Pinterest and YouTube. Collectively, these social media sites receive a lot of attention in popular culture and business news. There is also small industry of consultants and marketers that promise to help companies understand social media opportunities, and to design and implement social media programs.

What are the commonly-offered promises of social media for transit?

These are some of the purposes that are offered for social media in transit:

- Disseminate transit service advisories.

- Support customer service:

- Collect feedback from customers.

- Respond to customer questions and requests.

- Support good public relations:

- Engage with online conversations about transit; help steer online conversations.

- Create goodwill and build support for specific projects.

- Humanize the organization.

Does social media deliver on these promises?

I have concluded that social media can support some of these goals, but has more limited potential than some of its advocates suggest. To consider the benefit and usefulness of technologies it is most helpful to consider them in specific applications. The following 3 sub-sections considers some of these applications.

Purpose: Disseminate transit service alerts/advisories.

Usefulness: Marginal.

Current practice: Some agencies publish service alerts exclusively through social media, while others publish service alerts through various channels. (examples: @NJ_TRANSIT, @mbtaGM, @fbartalert). The TCRP Synthesis Report 99, “Uses of Social Media in Public Transportation” posits “Twitter is exceptionally well suited to providing service alerts, and many transit operators use it for this purpose.”

Evaluation: Despite the fact that the practice of disseminating service alerts through social media is widespread among transit agencies, this does not mean it is the most effective way of disseminating service alerts and exceptions. Here is why:

- Not everyone uses social media platforms: 67% of online adults say they use Facebook; 16% of online adults say they use Twitter (The Demographics of Social Media Users — 2012, Pew Internet & American Life Project).

- Many social media users are sporadic users. Some users may access social media sites multiple times per day, while others may log in occasionally (every few days). Further, almost two-thirds of Facebook users report intentionally “taking a break” from the site for a period of several days or more (“Coming and going on Facebook”, Pew Internet & American Life Project). Sporadic access makes social media a less reliable mode to communicate service information.

- Targeted text message and email alerts can provide information to a broader audience, and with greater reliability. More online Americans use email than social networking every day (Online activities report, Pew Internet & American Life Project). Using myself as one case (granted, this is often dangerous to do), I often go several days without checking Twitter or Facebook, but never more than a few hours without checking my email when I am in the office. When I go somewhere, I usually have my phone with me and am able to send and receive text messages. More people have email accounts than social media accounts, so the potential audience for email alert systems is bigger. For an example from a large agency, consider BART (San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit). In 2011, BART had more than 167,000 subscribers to its opt-in SMS (text) and email lists and bart.gov had 14 million visitors per year (Melissa Jordan’s presentation at the California Transit Association, 2011 – broken link after CTA updated their website). Meanwhile, approximately 4,400 people follow @SFBARTAlert on twitter as of March 2013. (As of the same time, approximately 30,500 people follow @SFBART, an account which publishes more general BART updates.)

- Social media mainly supports a “firehose” approach to providing service alerts: blasting a unfiltered alerts in a high-volume stream. This means that service alerts for an entire system are published in a Facebook or Twitter feed. Since passengers only use a few routes and stops, most of those alerts will not be relevant to them: this makes service alerts delivered through social media platforms less useful and efficient for passengers; it also creates the potential that passengers will start to ignore updates from the transit agency if they become accustomed to “filtering out” messages that are not relevant to them. One way that transit agencies narrow and target the “firehose” output is by creating separate accounts for separate lines or categories of service (for an example see @NYCtrains). However, there is an inherent limit to this approach — it is usually not feasible to create social media accounts for specific stops or stations because there can be so many

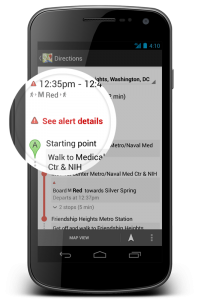

- A “faucet”, rather than “firehose”, approach offers greater potential utility for customers. A faucet approach gives customers the specific subset of alert information information they need — targeted by route, stop, or journey. This makes finding and accessing relevant information easier; I expect that it increases the likelihood that passengers will see advisory information. GTFS-realtime data feeds allow messages to be defined as pertaining to particular routes, trips, or stops. 3rd party applications like Google Maps (more information about live transit alerts in Google Maps on the Google blog) can then show those service alerts only in the relevant context. Mygistics TrafficBug provides a non-transit example of a highly personalized alerts system. The product provides notifications if there are traffic disruptions for a user’s common driving commute trips.

Part of its appeal to transit agencies of using social media for disseminating service alerts is that it is inexpensive and quick to implement. Facebook, Twitter, and Google provide and maintain the infrastructure for free. However, this may be a case of “getting what you pay for”: social media appears to be far from an ideal medium for disseminating service alerts.

This is not to say that social media should not be used for providing service alerts. However, it is inadequate to provide service alerts exclusively through social media. Diverse customers may want to get information in different ways. For example, some BART riders requested the @SFBARTAlert Twitter account, which has comparatively few followers (about 5,000 as of April 2013) to BART’s other service alert dissemination channels. However, BART’s customized software publishes alerts to Twitter automatically, so there is no additional burden on agency staff.

Purpose: Support customer service

Usefulness: Demonstrated utility in various industries: social media can offer unique opportunities compared to other communication modes.

Some transit agencies as well as many non-transit businesses use social media as a communications platform for customer service. Social media presents some unique opportunities:

- Some customers are inclined to turn to social media to gripe about problems with products and services. If they can direct these comments toward a staffed customer service account, then the transit agency has an opportunity to intercept an otherwise potentially embarrassing rant and productively respond.

- Social media platforms facilitate brief, focused communication, which may offer utility for making customer service more efficient.

- Conducting customer service conversations “in the open” helps customers feel the agency is accountable and transparent. A common refrain that I have heard is that this is helpful to create a “narrative of shared pain” and help customers feel that their concerns are taken seriously.

The TCRP report I mentioned earlier describes TransLink’s (Vancouver BC) motivation, experience, and practice using social media for customer service:

“Looking for other opportunities to use Twitter, employees saw an opportunity to tap into their experience connecting with riders during the Olympics. Staff proposed developing a Twitter communications channel to complement the agency’s customer service call center. They built a business case to get internal approval to add a dedicated position, including statistics about the growth in the volume of Twitter followers and the number of commendations the agency received lauding its social media efforts. In November 2010, TransLink integrated Twitter into its customer service group for one-month pilot test, which was subsequently extended indefinitely.”

Some organizations manage customer service queries through a primary social media account. Others create another account just for customer service. Just the other day, I corresponded with Delta Airlines through their @deltaassist Twitter account. Delta customer service very quickly responded to my brief request, making me a happier customer.

Carticulate’s blog post “How public transit should use social media” offers a useful survey. UTA (Salt Lake City, Utah) offers another example of social media-based customer service in action:

In Salt Lake City RideUTA communicates with their riders on a daily basis answering questions about service changes, where to find a stop, and answering questions about possible smelly cars (no kidding). Additionally their Twitter service helps to report back any issues with service that may arrise such as an accident in a bus lane or other issues that happen along a route. With this information coming directly from the transit agency it acts as an official response and also puts a personality on the agency by communicating promptly and directly with their riders.

An online service such as HootSuite can be very useful for managing incoming and outgoing social media communication across multiple social media sites, shared among multiple staff members. There are a several other choices including TweetDeck, SocialEngage, and others (see survey from pingdom).

While social media has utility for customer service, it does not reinvent the process of communicating and providing good service: (1) provide clear, timely information; and (2) respond to customer questions and concerns quickly and helpfully. Good customer service can (and in our modern age, probably must be) provided through a variety of electronic media.

People communicate through a growing diversity of (electronic) communication modes. Successful communications strategies allow people to use their preferred communication modes — email for some, phone for some, social media for others — in a way that is efficient and does not create unreasonable new burdens for the transit agency.

Purpose: Support good public relations

Usefulness: Some potential

Some transit agencies use social media as a complement to traditional media to maintain community and press relations. This can be a useful way to plant stories, for example, if journalists in your area actively participate in social media. Social media offers potential as a platform to build support for projects or your agency, or just build awareness of transit service.

The Carticulate blog post (referenced earlier) provides a nice example from Denver RTD.

“If you take about ten minutes to research the history of public transit in your city you are more often than not going to find that the public transit system that existed in the past was more robust than what exists today. Denver is included in this group, which had a vast streetcar network that was replaced in favor of busses. Rather than having citizens reminisce about the glory days RTD has embraced the past and helps riders focus on the future.

Their Facebook page features a ‘then and now’ photo series that shows past transit locations, services, and infrastructure and then features a new project showing the future of travel in their community. Additionally there are other photo contests and post telling where riders can voice their opinions at public meetings. All in all their page shows an eye towards the future and pushes for involvement from their riders.”

What is the larger context of communications systems that social media fits into?

On December 14, 2012, the New York Times published an article titled “Social Media Strategy Was Crucial as Transit Agencies Coped with Hurricane”. The article details failures and successes in the efforts of New Jersey Transit and Long Island Rail Road to provide customers information through Facebook and Twitter in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. The article isolates social media, and in so doing fails to call attention to a larger lesson: customers care about receiving accurate and timely information regardless of the medium. There are several mediums for communicating this information: email lists, text message alerts, agency websites, traditional media, and yes, social media. A more honest and complete story would would have considered the difference in transit agencies’ overall communication responses following Hurricane Sandy.

My criticism of much of the social media hype is that it is most frequently isolated in discussions like in the New York Times article. This “tool-first” approach suggests we grab a hammer and then see everything as a nail.

Let’s put it in context of an overall communications platform. This chart attempts to organize the various goals of transit agency communications programs, and the technologies that can support those goals. Goals are intentionally arranged in a hierarchy beginning with the most essential — easy-to-use information about services in the form of maps and timetables.

| Goal | Supporting technologies |

| Provide essential service information: Schedules and maps that are clear and easy-to-understand, online and in print | Paper materials, website |

| Provide tools that automate trip planning, and simplify using the service: Additional systems and features that make the service easier for customers to understand and use. | Phone-based call center, email and social media based customer support, online trip planner such as Google Maps, OpenTripPlanner, or 3rd party applications |

Provide supplemental service information that enhances the experience of using the service:

|

|

| Create broad partnerships and conduct marketing, outreach, and community engagement: Reach new customers through traditional marketing channels and through partnerships with local businesses and organizations. Maintain relationships to open the door to productive partnership opportunities. | Website, social media networks, email lists, offline connections. Note that much of this is accomplished offline, and through personal connections that are maintained with many communication technologies. |

| Provide personalized information: Engage with current and potential customers directly through personalized marketing, whether in-person, through mailed media, or online. | Direct mail, text message systems, email, mobile apps. |

Start with the purpose, then match the tool

In the end, I advocate that we put aside “technology-centric” discussions and investigations, and instead be clear about the goals of communications programs, subsequently proceeding by finding the best technologies and approaches. In other words, ask “What tactics and tools can we use and develop to (a) disseminate service advisories, (b) support customer service, and (c) support good public relations” rather than “What can we do with social media?”

It is the same idea that Jarrett Walker (humantransit.org) has put forward with regard to the bus vs. rail question (“a technophile wants my brain, and yours”) — put mobility need first and let technology choice follow. Let’s avoid technophilia — attachment to particular technologies — so that our search for the best tools can be guided by more objective assessments.

Further survey of social media use in transit

Social media practices in public transportation are still emerging. Susan Bregman curates a useful directory of transit agency social media accounts at thetransitwire.com.

One thought on “Getting real about the utility of social media for public transit”